System of linear equations

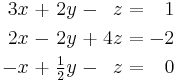

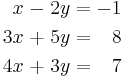

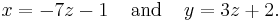

In mathematics, a system of linear equations (or linear system) is a collection of linear equations involving the same set of variables. For example,

is a system of three equations in the three variables  ,

,  ,

,  . A solution to a linear system is an assignment of numbers to the variables such that all the equations are simultaneously satisfied. A solution to the system above is given by

. A solution to a linear system is an assignment of numbers to the variables such that all the equations are simultaneously satisfied. A solution to the system above is given by

since it makes all three equations valid.[1]

In mathematics, the theory of linear systems is a branch of linear algebra, a subject which is fundamental to modern mathematics. Computational algorithms for finding the solutions are an important part of numerical linear algebra, and such methods play a prominent role in engineering, physics, chemistry, computer science, and economics. A system of non-linear equations can often be approximated by a linear system (see linearization), a helpful technique when making a mathematical model or computer simulation of a relatively complex system.

Contents |

Elementary example

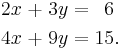

The simplest kind of linear system involves two equations and two variables:

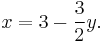

One method for solving such a system is as follows. First, solve the top equation for  in terms of

in terms of  :

:

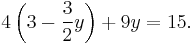

Now substitute this expression for x into the bottom equation:

This results in a single equation involving only the variable  . Solving gives

. Solving gives  , and substituting this back into the equation for

, and substituting this back into the equation for  yields

yields  . This method generalizes to systems with additional variables (see "elimination of variables" below, or the article on elementary algebra.)

. This method generalizes to systems with additional variables (see "elimination of variables" below, or the article on elementary algebra.)

General form

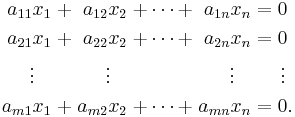

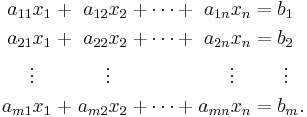

A general system of m linear equations with n unknowns can be written as

Here  are the unknowns,

are the unknowns,  are the coefficients of the system, and

are the coefficients of the system, and  are the constant terms.

are the constant terms.

Often the coefficients and unknowns are real or complex numbers, but integers and rational numbers are also seen, as are polynomials and elements of an abstract algebraic structure.

Vector equation

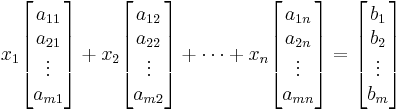

One extremely helpful view is that each unknown is a weight for a column vector in a linear combination.

This allows all the language and theory of vector spaces (or more generally, modules) to be brought to bear. For example, the collection of all possible linear combinations of the vectors on the left-hand side is called their span, and the equations have a solution just when the right-hand vector is within that span. If every vector within that span has exactly one expression as a linear combination of the given left-hand vectors, then any solution is unique. In any event, the span has a basis of linearly independent vectors that do guarantee exactly one expression; and the number of vectors in that basis (its dimension) cannot be larger than m or n, but it can be smaller. This is important because if we have m independent vectors a solution is guaranteed regardless of the right-hand side, and otherwise not guaranteed.

Matrix equation

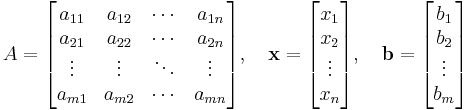

The vector equation is equivalent to a matrix equation of the form

where A is an m×n matrix, x is a column vector with n entries, and b is a column vector with m entries.

The number of vectors in a basis for the span is now expressed as the rank of the matrix.

Solution set

A solution of a linear system is an assignment of values to the variables x1, x2, ..., xn such that each of the equations is satisfied. The set of all possible solutions is called the solution set.

A linear system may behave in any one of three possible ways:

- The system has infinitely many solutions.

- The system has a single unique solution.

- The system has no solution.

Geometric interpretation

For a system involving two variables (x and y), each linear equation determines a line on the xy-plane. Because a solution to a linear system must satisfy all of the equations, the solution set is the intersection of these lines, and is hence either a line, a single point, or the empty set.

For three variables, each linear equation determines a plane in three-dimensional space, and the solution set is the intersection of these planes. Thus the solution set may be a plane, a line, a single point, or the empty set.

For n variables, each linear equations determines a hyperplane in n-dimensional space. The solution set is the intersection of these hyperplanes, which may be a flat of any dimension.

General behavior

In general, the behavior of a linear system is determined by the relationship between the number of equations and the number of unknowns:

- Usually, a system with fewer equations than unknowns has infinitely many solutions or sometimes unique sparse solutions (Compressed Sensing). Such a system is also known as an underdetermined system.

- Usually, a system with the same number of equations and unknowns has a single unique solution.

- Usually, a system with more equations than unknowns has no solution. Such a system is also known as an overdetermined system.

In the first case, the dimension of the solution set is usually equal to n − m, where n is the number of variables and m is the number of equations.

The following pictures illustrate this trichotomy in the case of two variables:

-

One Equation Two Equations Three Equations

The first system has infinitely many solutions, namely all of the points on the blue line. The second system has a single unique solution, namely the intersection of the two lines. The third system has no solutions, since the three lines share no common point.

Keep in mind that the pictures above show only the most common case. It is possible for a system of two equations and two unknowns to have no solution (if the two lines are parallel), or for a system of three equations and two unknowns to be solvable (if the three lines intersect at a single point). In general, a system of linear equations may behave differently than expected if the equations are linearly dependent, or if two or more of the equations are inconsistent.

Properties

Independence

The equations of a linear system are independent if none of the equations can be derived algebraically from the others. When the equations are independent, each equation contains new information about the variables, and removing any of the equations increases the size of the solution set. For linear equations, logical independence is the same as linear independence.

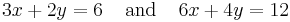

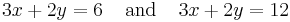

For example, the equations

are not independent — they are the same equation when scaled by a factor of two, and they would produce identical graphs. This is an example of equivalence in a system of linear equations.

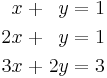

For a more complicated example, the equations

are not independent, because the third equation is the sum of the other two. Indeed, any one of these equations can be derived from the other two, and any one of the equations can be removed without affecting the solution set. The graphs of these equations are three lines that intersect at a single point.

Consistency

The rows of a linear system are consistent if they possess a common solution, and inconsistent otherwise. When the equations are inconsistent, it is possible to derive a contradiction from the equations, such as the statement that 1 = 3.

For example, the equations

are inconsistent. In attempting to find a solution, we tacitly assume that there is a solution; that is, we assume that the value of x in the first equation must be the same as the value of x in the second equation (the same is assumed to simultaneously be true for the value of y in both equations). Applying the substitution property (for 3x+2y) yields the equation 6 = 12, which is a false statement. This therefore contradicts our assumption that the system had a solution and we conclude that our assumption was false; that is, the system in fact has no solution. The graphs of these equations on the xy-plane are a pair of parallel lines.

It is possible for three linear equations to be inconsistent, even though any two of the equations are consistent together. For example, the equations

are inconsistent. Adding the first two equations together gives 3x + 2y = 2, which can be subtracted from the third equation to yield 0 = 1. Note that any two of these equations have a common solution. The same phenomenon can occur for any number of equations.

In general, inconsistencies occur if the left-hand sides of the equations in a system are linearly dependent, and the constant terms do not satisfy the dependence relation. A system of equations whose left-hand sides are linearly independent is always consistent.

Equivalence

Two linear systems using the same set of variables are equivalent if each of the equations in the second system can be derived algebraically from the equations in the first system, and vice-versa. Equivalent systems convey precisely the same information about the values of the variables. In particular, two linear systems are equivalent if and only if they have the same solution set.

Solving a linear system

There are several algorithms for solving a system of linear equations.

Describing the solution

When the solution set is finite, it is reduced to a single element. In this case, the unique solution is described by a sequence of equations whose left hand sides are the names of the unknowns and right hand sides are the corresponding values, for example  . When an order on the unknowns has been fixed, for example the alphabetical order the solution may be described as a vector of values, like

. When an order on the unknowns has been fixed, for example the alphabetical order the solution may be described as a vector of values, like  for the previous example.

for the previous example.

It can be difficult to describe a set with infinite solutions. Typically, some of the variables are designated as free (or independent, or as parameters), meaning that they are allowed to take any value, while the remaining variables are dependent on the values of the free variables.

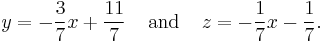

For example, consider the following system:

The solution set to this system can be described by the following equations:

Here z is the free variable, while x and y are dependent on z. Any point in the solution set can be obtained by first choosing a value for z, and then computing the corresponding values for x and y.

Each free variable gives the solution space one degree of freedom, the number of which is equal to the dimension of the solution set. For example, the solution set for the above equation is a line, since a point in the solution set can be chosen by specifying the value of the parameter z. An infinite solution of higher order may describe a plane, or higher dimensional set.

Different choices for the free variables may lead to different descriptions of the same solution set. For example, the solution to the above equations can alternatively be described as follows:

Here x is the free variable, and y and z are dependent.

Elimination of variables

The simplest method for solving a system of linear equations is to repeatedly eliminate variables. This method can be described as follows:

- In the first equation, solve for one of the variables in terms of the others.

- Plug this expression into the remaining equations. This yields a system of equations with one fewer equation and one fewer unknown.

- Continue until you have reduced the system to a single linear equation.

- Solve this equation, and then back-substitute until the entire solution is found.

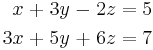

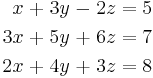

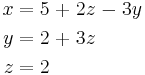

For example, consider the following system:

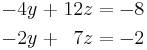

Solving the first equation for x gives x = 5 + 2z − 3y, and plugging this into the second and third equation yields

Solving the first of these equations for y yields y = 2 + 3z, and plugging this into the second equation yields z = 2. We now have:

Substituting z = 2 into the second equation gives y = 8, and substituting z = 2 and y = 8 into the first equation yields x = −15. Therefore, the solution set is the single point (x, y, z) = (−15, 8, 2).

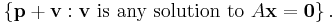

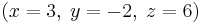

Row reduction

In row reduction, the linear system is represented as an augmented matrix:

This matrix is then modified using elementary row operations until it reaches reduced row echelon form. There are three types of elementary row operations:

- Type 1: Swap the positions of two rows.

- Type 2: Multiply a row by a nonzero scalar.

- Type 3: Add to one row a scalar multiple of another.

Because these operations are reversible, the augmented matrix produced always represents a linear system that is equivalent to the original.

There are several specific algorithms to row-reduce an augmented matrix, the simplest of which are Gaussian elimination and Gauss-Jordan elimination. The following computation shows Gauss-Jordan elimination applied to the matrix above:

The last matrix is in reduced row echelon form, and represents the system x = −15, y = 8, z = 2. A comparison with the example in the previous section on the algebraic elimination of variables shows that these two methods are in fact the same; the difference lies in how the computations are written down.

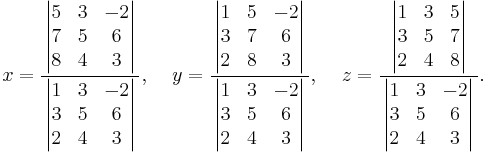

Cramer's rule

Cramer's rule is an explicit formula for the solution of a system of linear equations, with each variable given by a quotient of two determinants. For example, the solution to the system

is given by

For each variable, the denominator is the determinant of the matrix of coefficients, while the numerator is the determinant of a matrix in which one column has been replaced by the vector of constant terms.

Though Cramer's rule is important theoretically, it has little practical value for large matrices, since the computation of large determinants is somewhat cumbersome. (Indeed, large determinants are most easily computed using row reduction.) Further, Cramer's rule has very poor numerical properties, making it unsuitable for solving even small systems reliably, unless the operations are performed in rational arithmetic with unbounded precision.

Other methods

While systems of three or four equations can be readily solved by hand, computers are often used for larger systems. The standard algorithm for solving a system of linear equations is based on Gaussian elimination with some modifications. Firstly, it is essential to avoid division by small numbers, which may lead to inaccurate results. This can be done by reordering the equations if necessary, a process known as pivoting. Secondly, the algorithm does not exactly do Gaussian elimination, but it computes the LU decomposition of the matrix A. This is mostly an organizational tool, but it is much quicker if one has to solve several systems with the same matrix A but different vectors b.

If the matrix A has some special structure, this can be exploited to obtain faster or more accurate algorithms. For instance, systems with a symmetric positive definite matrix can be solved twice as fast with the Cholesky decomposition. Levinson recursion is a fast method for Toeplitz matrices. Special methods exist also for matrices with many zero elements (so-called sparse matrices), which appear often in applications.

A completely different approach is often taken for very large systems, which would otherwise take too much time or memory. The idea is to start with an initial approximation to the solution (which does not have to be accurate at all), and to change this approximation in several steps to bring it closer to the true solution. Once the approximation is sufficiently accurate, this is taken to be the solution to the system. This leads to the class of iterative methods.

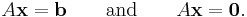

Homogeneous systems

A system of linear equations is homogeneous if all of the constant terms are zero:

A homogeneous system is equivalent to a matrix equation of the form

where A is an m × n matrix, x is a column vector with n entries, and 0 is the zero vector with m entries.

Solution set

Every homogeneous system has at least one solution, known as the zero solution (or trivial solution), which is obtained by assigning the value of zero to each of the variables. The solution set has the following additional properties:

- If u and v are two vectors representing solutions to a homogeneous system, then the vector sum u + v is also a solution to the system.

- If u is a vector representing a solution to a homogeneous system, and r is any scalar, then ru is also a solution to the system.

These are exactly the properties required for the solution set to be a linear subspace of Rn. In particular, the solution set to a homogeneous system is the same as the null space of the corresponding matrix A.

Relation to nonhomogeneous systems

There is a close relationship between the solutions to a linear system and the solutions to the corresponding homogeneous system:

Specifically, if p is any specific solution to the linear system Ax = b, then the entire solution set can be described as

Geometrically, this says that the solution set for Ax = b is a translation of the solution set for Ax = 0. Specifically, the flat for the first system can be obtained by translating the linear subspace for the homogeneous system by the vector p.

This reasoning only applies if the system Ax = b has at least one solution. This occurs if and only if the vector b lies in the image of the linear transformation A.

See also

- LAPACK (the free standard package to solve linear equations numerically; available in Fortran, C, C++)

- Row reduction

- Simultaneous equations

- Arrangement of hyperplanes

- Linear least squares

- Matrix decomposition

- Iterative refinement

Notes

- ^ Linear algebra, as discussed in this article, is a very well-established mathematical discipline for which there are many sources. Almost all of the material in this article can be found in Lay 2005, Meyer 2001, and Strang 2005.

References

Textbooks

- Axler, Sheldon Jay (1997), Linear Algebra Done Right (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0387982590

- Lay, David C. (August 22, 2005), Linear Algebra and Its Applications (3rd ed.), Addison Wesley, ISBN 978-0321287137

- Meyer, Carl D. (February 15, 2001), Matrix Analysis and Applied Linear Algebra, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM), ISBN 978-0898714548, http://www.matrixanalysis.com/DownloadChapters.html

- Poole, David (2006), Linear Algebra: A Modern Introduction (2nd ed.), Brooks/Cole, ISBN 0-534-99845-3

- Anton, Howard (2005), Elementary Linear Algebra (Applications Version) (9th ed.), Wiley International

- Leon, Steven J. (2006), Linear Algebra With Applications (7th ed.), Pearson Prentice Hall

- Strang, Gilbert (2005), Linear Algebra and Its Applications

External links

- WebApp descriptively solving systems of linear equations with a number of methods

- Solving system linear equations online matrix calculator and tutorial.

- Online Equations Solver

- Online linear solver

- Online Calculator of System of linear equations

|

||||||||||||||

![\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

3 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 8

\end{array}\right]\text{.}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b45abba6102620b7d6a2e1a56759f0e7.png)

![\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

3 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 8

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7726f6c074387e180a3695097c2cb6a8.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

0 & -4 & 12 & -8 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 8

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f5cba6770716799dca4b78630c3c1756.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

0 & -4 & 12 & -8 \\

0 & -2 & 7 & -2

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e37941df9c79e9adc8af087af9534e13.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

0 & 1 & -3 & 2 \\

0 & -2 & 7 & -2

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a9e9028b501af962575c63aa4591a3e1.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

0 & 1 & -3 & 2 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0a6f0ad7cc1a970c8fbc0fbba7a22d6c.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & -2 & 5 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 8 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f135ac713c574912d630c0a0b769ebb2.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 3 & 0 & 9 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 8 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e12d739e6678662924ae5d09f0554155.png)

![\sim

\left[\begin{array}{rrr|r}

1 & 0 & 0 & -15 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 8 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f000bc7d77fa2ae002d5000f8d38aaa8.png)